An exhibition at the Museum Kebaharian Jakarta (Jakarta’s Maritime Museum) invites visitors to confront a layered, uncomfortable, and deeply relevant past. Crimson Gilt, a site-specific installation by Amsterdam-based artist Vincent Ruijters, runs from 7 February to 7 April 2026, offering a transnational re-reading of maritime and colonial history through art, space, and collective memory.

Ruijters, known for his poetic, conceptual, and technologically inflected installations, positions this project across three countries that were once connected through the vast trading network of the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie): Japan, Indonesia, and the Netherlands. Each chapter of the exhibition is staged in a historically charged site, the former VOC trading post in Hirado, the Museum Kebaharian Jakarta, and the National Maritime Museum in Amsterdam. In Crimson Gilt, space is not merely a venue but an active narrative element, preserving and activating colonial memory.

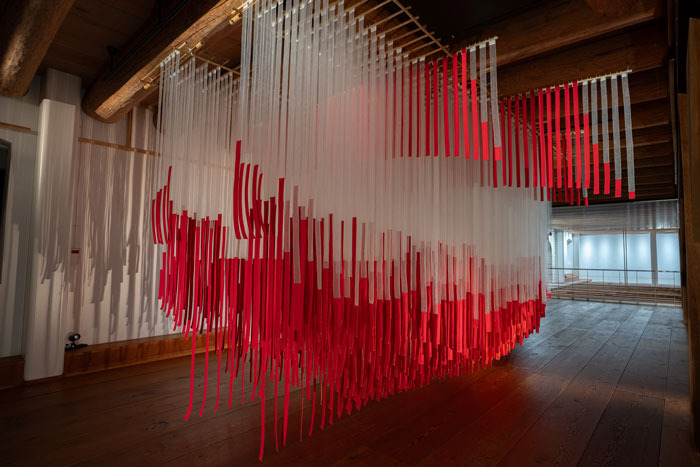

At the centre of the project is an illusory, floating textile ship, a replica of the Amsterdam, a VOC vessel built in 1748 that famously sank on its maiden voyage to Batavia. The ship carries a contradictory legacy. It is celebrated in Dutch and Japanese narratives as a symbol of maritime prowess yet condemned in Indonesia as an emblem of exploitation and the beginning of three and a half centuries of colonial domination.

Ruijters articulates this tension through colour. In Jakarta, the ship appears red at the front and gold within, a stark visual metaphor for visible suffering and extracted wealth. In Hirado, Japan, the installation behaves differently. Viewed from the front, it gleeds in metallic gold. As visitors walk through it, the gold gradually transforms into a sombre blood red. The perceptual shift mirrors a historical one: Japan never experienced the VOC as a colonial power, while Indonesia endured its full force.

This contrast is central to Crimson Gilt’s curatorial framework. The exhibition does not merely recount history but asks how history is remembered differently across nations connected by the same maritime routes.

For Indonesia, ships once symbolised connection. They linked kingdoms, facilitated the exchange of ideas, and formed the basis of cultural and economic networks across islands. The arrival of the VOC fundamentally altered this symbolism. Ships became instruments of monopoly, control, and imperial expansion. Sea routes were seized, spice trade regulated, and trade agreements enforced under coercion. Over time, the ship’s symbolic place within Indonesian identity eroded.

As noted in the curatorial text: “The arrival of the VOC, which opened the door to colonialism in Indonesia, had long-term social and political impacts that remain relevant to this day. These practices later inherited ethnic stereotypes, social stratification, identity politics, and authoritarian tendencies that became the roots of various domestic conflicts.”

The VOC introduced rigid racial classifications that positioned Europeans as rulers, “Easterners” —Chinese, Arabs, and Indians— as economic intermediaries, and indigenous peoples as labourers and colonial subjects. It also embedded a centralised, divide-and-rule political structure whose echoes remain traceable in contemporary social and political dynamics.

Crimson Gilt uses the figure of the ship as a historiographical device. It reactivates spatial memory and encourages trilateral dialogue between countries within the VOC maritime network, aligning perceptions and opening space for reflection, and perhaps healing. The exhibition suggests that art can function not only as aesthetic experience but as a site for knowledge production and the negotiation of collective memory.

The project’s timing is equally significant. The presentation in Hirado in 2025 formed part of the 400th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Japan and the Netherlands, a relationship that began at that very site in 1609. The Jakarta exhibition coincides with the approach to the city’s 500th anniversary (1527–2027), prompting renewed public and institutional reflection on its colonial past. Both institutions deliberately situated Crimson Gilt within broader diplomatic and historical frameworks, emphasising the continued relevance of cultural exchange in addressing historical narratives.

In Ruijters’ poetic reimagining, Amsterdam never sinks. Instead, it completes its journey, from Amsterdam to Hirado, to Jakarta, and back again, carrying with it the unresolved spirit of the VOC. The voyage becomes symbolic rather than historical, concluding a long colonial chapter not through erasure, but through confrontation and understanding.

In Crimson Gilt, the ship does not simply return to port. It returns to memory.

Museum Kebaharian Jakarta

Jl. Pasar Ikan No. 1, Penjaringan, North Jakarta

@museumkebaharianjkt

Exhibition Period:

7 February to 7 April 2026

From 9 am to 3 pm (Weekdays), 9 am to 8 pm (Weekends)

Monday closed.