Text by Cindy Julia Tobing, Images courtesy of Juliana Tan

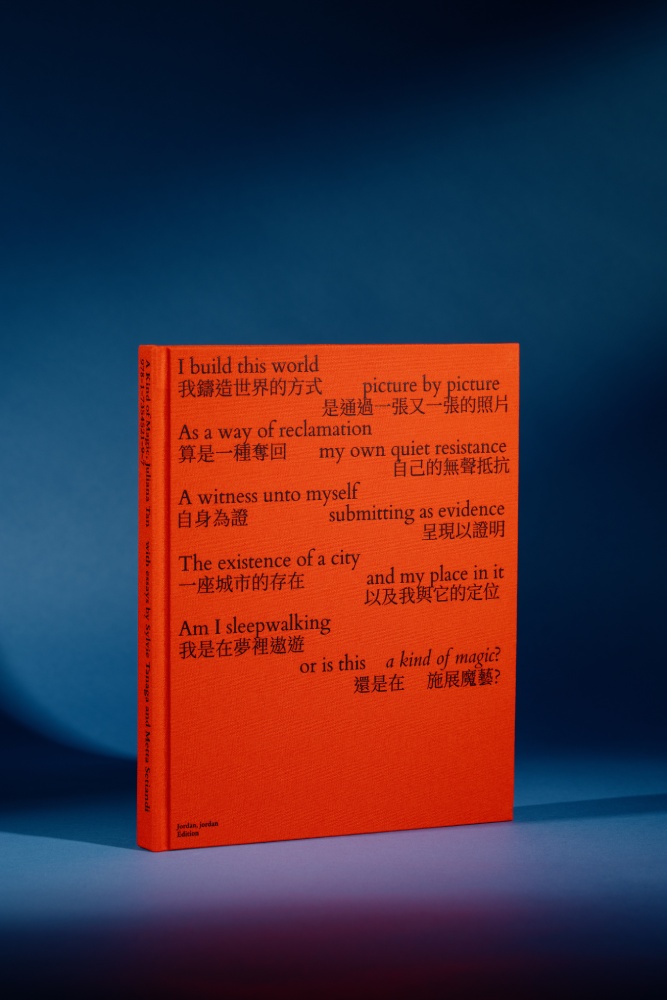

Juliana Tan’s award-nominated photobook, ‘A Kind of Magic’, revisits her childhood in Bandung before her displacement to Singapore, situating personal memory within the lasting impact of Indonesia’s 1998 unrest.

The children who grew up in the shadow of May 1998—a dark chapter of violence and racial tension in Indonesian history—are now finding the language and platform to articulate what those years left behind. Among them is Singapore-based photographer Juliana Tan, whose decade-in-the-making photobook, ‘A Kind of Magic’ (2025), revisits the places and lingering emotions of her childhood in Bandung before she and her family fled to Singapore for safety when she was nine.

Growing up in the city-state, Juliana went on to study Communications, Broadcast and Cinema Studies at Nanyang Technological University. She established a career as a photographer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, Monocle, Wired, and for brands ranging from Google and Netflix to Marina Bay Sands.

Her personal projects are just as expansive, from a travel compendium born out of a journey through nine countries and 33 cities, to a photo essay inspired by a fictional story that led her through various districts in Seoul.

Back in May 2025, Juliana launched the photobook at MET Glodok, a café–slash–studio in Jakarta’s Chinatown. She was joined by the book’s collaborators, publisher Jordan Marzuki of Jordan, jordan Édition; writer and researcher Sylvie Tanaga; and multidisciplinary artist and founder of MET Glodok, Metta Setiandi.

They also came from a generation that remembers, with unsettling clarity, where they were when the unrest broke out. This shared thread became the soul of the photobook — a work recently shortlisted for the prestigious 2025 Lucie Foundation Book Prize— weaving together Juliana’s personal and emotive images of the places that shaped her childhood, Sylvie’s research-driven essay on the Chinese Indonesian history and experience, and Metta’s own lived account of the riots that left a deep mark on Glodok, the historic Chinese Indonesian enclave that her family has called home for almost a century.

“When I was working on the book, I knew I wanted writing to help contextualise the project since [May 1998] didn’t only affect me,” said Juliana, whose photobook is written in English, Mandarin, and Bahasa Indonesia. “It fascinates me that people from my generation—whom I spoke to during the launch, or those who moved to Singapore—knew exactly where they were when it happened; some were pulled out of school, others watched their schools burn. We were kids then, and now, in our mid-career, we finally have the maturity to talk about it.”

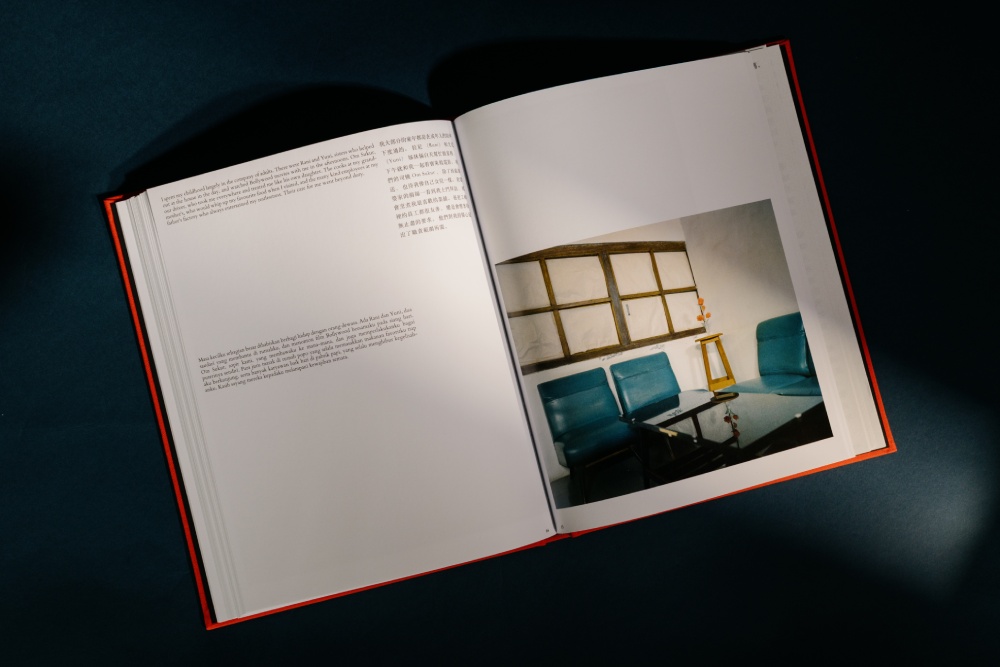

Visually, A Kind of Magic is comfortable in its quietness. Shot mostly on a medium-format film camera that Juliana carried on her repeated trips back to her hometown, the photobook follows the spaces that once felt vivid to her but now hold an emptiness she can bridge only through memory. “I left Indonesia when I was nine. At that age, you haven’t been to many places, so the locations in the book are those that were close to me: my home, my dad’s office, the hair salon my mother used to go to, my old school.”

A photograph shows a torn kite tangled in tree branches, an image Juliana links to her childhood memory of slipping off a roof while trying to retrieve one. Another photo captures a lonely street lined with an old-school dangdut pub and karaoke shopfront; Juliana herself never went there, but it reminds her of the karaoke place her father used to sneak her and her sister into and sing Chinese songs together. “When you work on a project for this long, you naturally feel the passing of time in the images. I find it quite beautiful.”

The timing of the photobook’s release felt especially resonant. In June 2025, during an interview with journalist Uni Lubis for IDN Times, Minister of Culture Fadli Zon sparked public backlash when he dismissed the documented cases of sexual violence against Chinese-Indonesian women during the 1998 riots as mere “rumour.” Sylvie’s essay gestures toward this longstanding pattern of erasure, noting in the book that “the historical contributions of the Chinese community remain unrecognised in the national curriculum.”

Just a week after Indonesia’s Independence Day in August 2025, mass demonstrations erupted in Jakarta over parliament’s new housing allowance, quickly escalating into clashes between students and police. For generations like Juliana’s, and those before hers, the scenes sounded off a familiar sense of alert.

“Even though the recent situation wasn’t about Chinese Indonesians specifically, you could feel how quickly things could turn in the heat of the moment. I even wondered, ‘Is history about to repeat itself?’ But I also saw people online reminding others not to fall into provocations, not to let those in power divide communities,” recounted Juliana, who was in Singapore at the time.

“I didn’t expect the recent events to suddenly contextualise the book again. Through A Kind of Magic, my hope is to create space for conversations, to have more stories told, and more voices heard. The more people speak up, the more courage others will have.”

In the process of making and publishing the book, Juliana faced moments of self-doubt and responses that underscored just how deeply the scars of May ’98 run within the Chinese Indonesian community. One realisation that surfaced was her own instinct toward self-censorship. Sylvie’s unflinching essay—especially its criticism of the Indonesian government—made her uneasy at first. “But Sylvie wasn’t afraid,” she recalled.

When she later showed the work to her mother, the reaction was telling: “Why did you have to rehash it?” It spoke to the deep-seated emotions that have shaped a long-standing culture of caution within older Chinese-Indonesian generations—a “keep your head down” mentality, as Juliana puts it.

Yet A Kind of Magic was not intended to be a vessel for old wounds. For Juliana, it is an act of personal resistance and an attempt to process the realities that shaped her childhood on her own terms. It is also why, counterintuitively, she associated the book with “magic”.

“May ‘98 did change my childhood, but I didn’t approach the work thinking, ‘I’m carrying trauma’. I call it magic because photography gave me a way to reclaim something that was taken away by forces beyond my control,” concluded Juliana. “The ability to revisit places that no longer exist, almost as if travelling through time, and now to see them with kindness and gentler eyes. That feels magical to me.”

Follow Juliana on Instagram: @julianatan.co