Photo credit by Andreas Widi, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

This article is part of a long-form feature ‘Spaces to Sink Into’, on how design contributes to comfort and wellbeing, in our January-February 2026 Edition ‘Living Slow in a Fast City’. Download the edition free here.

Rumour has it that fast food chains in the past used uncomfortable furniture and clashing colours to encourage diners to leave quickly, ensuring there were empty tables for the next round of punters. It’s an unconventional use of design, but it’s certainly a crafty tactic, useful for that specific industry. Normally design is meant to entice us, and today that’s being applied to creating picturesque backdrops that seduce us to visit, be it a restaurant, retail store or a recreation park.

But looks don’t ensure liveability, and we’ve all been duped by ‘Instagrammable’ cafés that, upon arrival, feel completely void of atmosphere and warmth. Whilst aesthetics are important, designing for comfort and congeniality requires going beyond the visual, and to consider how one experiences, interacts and relates to the space around us.

“We use play features as a design strategy,” explains Daliana Suryawinata, co-founder of SHAU, an award-winning architecture and urbanism firm based out of Bandung and Rotterdam. The firm is working on a visionary long term project to build 100 Microlibraries across Indonesia by 2045, utilising the built environment to encourage reading in local communities whilst simultaneously showcasing social-climatic design solutions that suit a hyperlocal environment.

Their pilot project was Bima Microlibrary, built in 2016 in a small neighbourhood park in Bandung, in front of a concrete football area where the local children would often play. “Design isn’t necessarily what attracts them. The kids will play, notice the building and they’ll go upstairs, they’ll see the books, which lures them to start reading,” explains Daliana.

“It’s an implicit design strategy that we later used in other microlibraries,” adds Florian Heinzelmann, also co-founder at SHAU. “We tried to incorporate play features – swings, slides, nets – to attract more kids, because if they have a good time there, they’ll want to come back, and hopefully spend time reading.”

Since 2016, seven microlibraries have been completed, each in small neighbourhoods from Bojonegoro, East Java to Semarang, Central Java, with more on the way. Measuring between 80 to 160 square metres, SHAU had to consider how these libraries would not only attract local children in, but how to make sure they felt comfortable there, using design to ensure their long term use as a place to read and gather.

Photo by Kie, courtesy of SHAU

Photo by Kie, courtesy of SHAU

They considered where the children would be reading, and integrated features that made the spaces feel relaxed, homey and informal. At Warak Kayu Microlibrary, Semarang, a hanging net space allows for dreamy, lounging reads; at Bima, carpets entice spreading across on the floor, as children like to do; and at Hanging Gardens, also in Bandung, Florian was inspired by the German kuschelecke, or cosy corner, creating a tight nook space with cushioned floors made to feel like a ‘kids only’ safe zone. Other aspects like ensuring natural light, but without too much glare, or softly infusing nature into the design were other considered elements. Together with the play features, children could feel like the microlibraries was a space built for them.

Situated in rural or small neighbourhoods, there was one aspect SHAU wanted to get just right. “Thermal comfort in the tropics is so important,” says Florian, who emphasises that reasonable temperature is integral to the psychological comfort of a space.

You Might Also Like: Function Before Form: Designer Lianggono on Creating Comforting Spaces

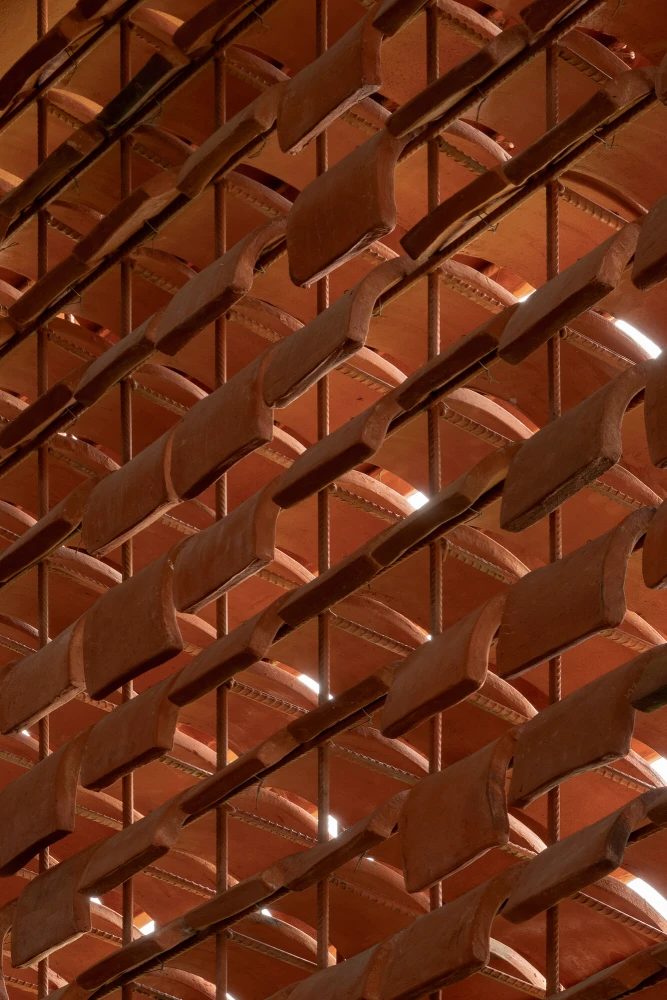

“It starts with the orientation of the building, minimising the east-west façade, which has the highest solar radiation; considering possibilities for cross-ventilation; creating large overhangs to increase shading. It depends on the local conditions of course – Bandung highlands require a different strategy than a hot urban centre in Surabaya or Jakarta.” Each of the libraries also has its own ‘double skin’ feature, made to protect against weather conditions, be it sun heat or rain. The façades don’t only mitigate against weather, they also become each building’s external expression, both aesthetically but also in material statement.

“At Bima, the façade utilises upcycled white plastic ice cream buckets,” shares Daliana, pointing out the mesmerising grid of translucent, window-like squares that surround the entire floor. “This was a statement about material value – don’t just throw away plastic waste, it can be both useful and beautiful. In Semarang, the microlibrary is made fully from FSC-certified wood, and whilst wood may have been normal in traditional architecture, building with wood is rare in modern practices. So, we returned to this but in the most sustainable way” says Daliana.

Passive climate designs and material experimentation is in fact where SHAU excels, they are recognised for utilising the built environment to shape behaviour, build climate awareness and change perceptions. It’s what they call ‘social-climatic design’, in which architecture can address community and environmental issues simultaneously. The approach has won them global awards – most recently the Ammodo Award for Social Architecture 2025 and the Architizer A+ Awards in 2025 – but also major projects, including the design of the Vice Presidential Palace in the IKN, which they are currently working on, as well as an upcoming Performing Arts Centre in Jakarta (watch this space).

But the urban designers have learned lessons along the way, discovering interesting factors that dictate people’s sense of comfort and how they engage with public spaces. At Alun-Alun Cicendo Park, Bandung, they worked with the surrounding blacksmiths and local steel shops to create the outdoor furnishings, who later would use the park themselves as they felt a ‘proud sense of belonging’ – “If a space is given to you, you don’t own it, but if you’re involved in the process, you do,” adds Florian. At The Film Park, a public screening facility underneath a flyover in Bandung, they used artificial grass to cover the dynamic, sawah-like terraced amphitheatre seating, a material choice that saw decreases in littering and people taking off their shoes. The carpet-like grass made people feel they were indoors, in a living room, and therefore respected the cleanliness of the space more.

As for the microlibraries, with each location, SHAU learns a little more, developing how features, materials and design can further entice children to read, whilst exploring new sustainable materials that suit hyperlocal climates and environments. “We find it important to create designs that respond to current issues. I hope more architects create projects focused on impact,” Daliana closes.