Indonesia is a country rich in history and culture, with many ancient temples scattered throughout the archipelago. One of them is the majestic Prambanan temple located in Central Java, which is considered one of the most important Hindu temples in Southeast Asia. The complex is a testament to the ancient Javanese civilisation, and is a symbol of Indonesia’s rich heritage. It has become a popular destination for Indonesians and international tourists alike.

Let’s dive into the history and significance of the magnificent Prambanan temple.

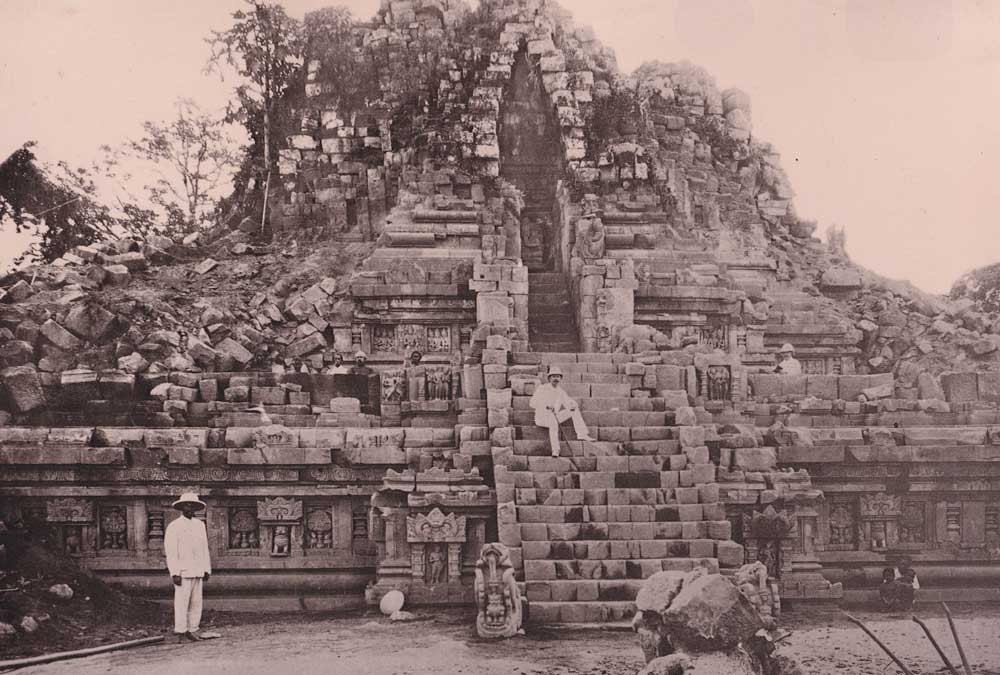

A photograph taken around the year 1890 showing an excavated temple. People with a good eye can spot eleven people posing in the picture. (Kassian Cephas – Indies Gallery Collection)

We describe Prambanan’s origin and construction, its sudden profusion and thousand years of decay leading up to its rediscovery and restoration of this now UNESCO World Heritage Site. Prambanan is a true masterpiece of the classical period in Indonesia.

In this article, we highlight a number of authentic 1893 photographs, which show the result of the excavation, shortly after its formal rediscovery in the 1880s. The photographs are taken by Kassian Cephas, a Javanese photographer of the court of the Yogyakarta Sultanate.

Trained at the request of Sultan Hamengkubuwana VI, Cephas was the first Indonesian to become a professional photographer. After becoming a court photographer in early 1871, he began working on portrait photography for members of the royal family, but also made a large number of studio portraits and photographs of the daily life of the Javanese people, as well as documentary work for the Dutch Archaeological Union. His photographs are of huge importance for our knowledge of nineteenth-century Javanese cultural history.

We will look in more detail at the life and work of Kassian Cephas in an upcoming article for NOW! Jakarta. The photographs are in the Indies Gallery collection, and can be purchased through our website.

Prambanan – Origins and Construction

The Prambanan temple complex can be traced back to the 9th century AD, during the rule of the Sailendra dynasty in Central Java. The Sailendra dynasty was a Buddhist dynasty that had established itself as a major power in the region, and had built several impressive Buddhist temples, including the famous Borobudur temple, a few decades prior to Prambanan.

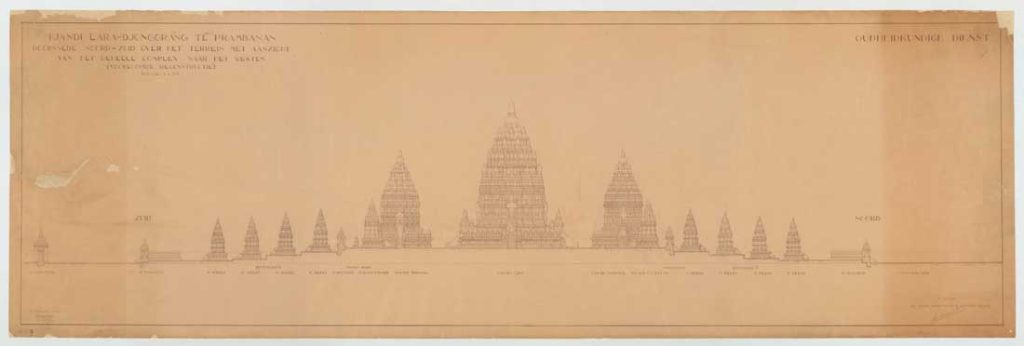

An architectural model of the Prambanan complex, which gives an idea of how it looked like with all its 240 temples.

However, in the mid-8th century, the Sailendra dynasty began to decline, and was eventually overthrown by the Sanjaya dynasty, a Hindu dynasty that had its capital in the nearby city of Mataram. The Sanjaya sought to establish its legitimacy by building a grand temple complex that would rival the Borobudur temple, and would be dedicated to the Hindu gods Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma. The construction of Prambanan saw a transition from a Buddhist to a Hindu style in the Mataram Kingdom.

Prambanan is believed to have been constructed between 850 and 900 AD. The construction of the temple is credited to Rakai Pikatan, a king of the Sanjaya dynasty, who is said to have been inspired by a dream in which Shiva appeared to him and commanded him to build a temple in his honour. The temple complex was built periodically and continued by other Mataram kings with no other Javanese temples ever surpassing its scale.

There are three main temples dedicated to Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma, as well as numerous smaller temples and shrines. The complex originally consisted of 240 temple structures, with its main temple, dedicated to Shiva, known as Loro Jonggrang, which means “slender maiden” in Javanese. It stands 47 metres tall, and is adorned with carvings and sculptures depicting scenes from Hindu mythology. The temple complex is surrounded by a large wall, which measures 390 metres in length and 310 metres in width.

Photograph showing the panels of narrative bas-reliefs, taken around the year 1890. (Kassian Cephas – Indies Gallery Collection)

The construction was a massive undertaking that involved the labour of thousands of workers using volcanic stone, which was cut and shaped by hand. The intricate carvings and sculptures that adorn the temples were also created by hand, utilising chisel and hammer.

Prambanan served as the royal temple of the Kingdom of Mataram, with most of the state’s religious ceremonies and sacrifices being conducted there. At the height of the kingdom, scholars estimate that hundreds of brahmins with their disciples lived within the outer wall of the temple compound. The urban centre and the court of Mataram were located nearby, somewhere in the Prambanan Plain.

The temple is adorned with panels telling the story of the Hindu epic Ramayana and Bhagavata Purana. The panels were carved along the inner balustrades wall on the gallery around the three main temples, and read from left to right. The story starts from the east entrance where visitors turn left and move around the temple gallery in a clockwise direction. This conforms to the ritual of circumambulation performed by pilgrims who move in a clockwise direction while keeping the sanctuary to their right.

Two (probably) Dutch men posing for the photograph taken around the year 1890 (Kassian Cephas – Indies Gallery Collection)

Prambanan Abandoned

The complex was abandoned in the 10th century after being in use less than a 100 years. The true reason behind its abandonment is unclear. It is known that the Javanese rulers of the Kingdom of Mataram moved their capital to the east of Java around the year 930, away from the Prambanan temple.

Is the transfer of the Mataram capital city or a power struggle a possible cause? Did violent volcanic eruptions in the region leave it abandoned?

These events marked the beginning of the decline and deterioration of the temple. The Javanese who lived in the area took the ancient stones from the temple to use them for building their own homes. The temple building began to crumble and collapse, and after an earthquake in the 16th century, the Prambanan temple became increasingly damaged.

Three Javanese men posing on an excavated temple, taken around the year 1890 (Kassian Cephas – Indies Gallery Collection)

Prambanan – Formal Rediscovery

The Javanese people who lived in the surrounding villages obviously knew about the temple ruins before formal rediscovery, but they did not know exact details about its historical background, which kingdoms ruled or which king commissioned the construction of the structures. As a result, they developed tales and legends to explain the origin of the temples, infused with myths of giants, and a cursed princess.

In 1733, when Java was under the rule of the VOC (Dutch East India Company), a Dutch colonial government employee provided a first report on the Prambanan temple in his journal. During his travels to visit Kartasura, then the capital of Mataram, he had the opportunity to visit the ruins of Prambanan, which he described as “Brahmin temples” that resemble a mountain of stones.

A circa 1890 photograph showing larger carvings and sculptures lined up in the forefront, of which many were taken away from the site. (Kassian Cephas – Indies Gallery Collection)

In 1803, the temple again attracted attention when Nicolaus Engelhard, the Dutch Governor of the northeast coast of Java, visited Prambanan. Impressed by the temple ruins, he commissioned clearing of the site from earth and vegetation, measuring the area, and made drawings of the temple. This was the first real effort to study and restore the temple.

In 1811, during the short-lived British occupation of the Dutch East Indies, a surveyor in the service of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (a British colonial official who served as the Governor of the Dutch East Indies between 1811 and 1816), came upon the temples by chance while travelling around Java. Although Sir Raffles commissioned a full survey of the ruins, they remained neglected for decades after the Dutch took back power in Java.

Dutch residents carried off sculptures as garden ornaments and Javanese continued to use the foundation stones for construction material. Half-hearted excavations by archaeologists in the 1880s adversely facilitated looting instead, as numbers of temple sculptures were taken away as collections.

Prambanan Restoration

In 1918, the Dutch colonial government began reconstruction plans, and proper restoration commenced in 1930. In the first year the Dutch East Indies Archaeological Service successfully restored two temples in the central court, and two smaller pervara temples by using the original stone blocks as much as possible.

The restoration efforts were hampered by the economic crisis in the 1930s, and came to a full stop due to the outbreak of World War II (1942-1945), and the following Indonesian National Revolution (1945-1949).

In 1949, despite many technical drawings and photographs being damaged or lost during the war, the temple reconstruction resumed. The reconstruction of the main Shiva temple was completed in 1953 and inaugurated by Indonesia’s first president Sukarno.

Since much of the original stonework has been stolen and reused at remote construction sites, and given the huge scale of the temple complex, the government decided to rebuild shrines only if at least 75% of their original masonry was available.

A Dutch 1933 reconstruction drawing of the cross section of the whole Prambanan temple compound. (Image: collection unknown)

The Brahma temple was reconstructed between 1978 and 1987. The Vishnu temple was rebuilt from 1982 to 1991. The Vahana temples of the eastern rows and some smaller shrines were completed from 1991 to 1993. In the early 1990s the government removed the market that had sprung up near the temple and redeveloped the surrounding villages and rice paddies as an archaeological park. The park covers a large area encompassing the whole Prambanan complex.

Finally by 1993, the whole towering main temples of the Prambanan central zone were erected and completed, simultaneously inaugurated by President Suharto.

As at early 2023, from the originally 224 temples, only 6 of them are completely reconstructed. Due to this massive scale and the sheer number of temples, the efforts at restoration still continue up to this day. If all of the 224 temples have to be restored completely, it might take up to 250 years, as reconstruction of one temple takes approximately 8 to 12 months to complete.

Photograph showing the panels of narrative bas-reliefs, taken around the year 1890. (Kassian Cephas – Indies Gallery Collection)

Nowadays, around a million people visit the Prambanan in Yogyakarta each year, to wonder about its grandeur of ancient Java’s art and architecture, a true masterpiece of the classical period in Indonesia. A must visit for those travelling to Java, Indonesia.

We hope to have given you a brief introduction to the majestic Prambanan temple complex, on which many books and studies are written, widely available for those interested.

The photographs shown in this article are offered for purchase by Indies Gallery, dealer in authentic maps, prints, books and photographs, dating from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. You will find the Prambanan photographs in the link : indiesgallery.com

Besides authentic maps and prints, Indies Gallery also offers reprints of a part of their collection, which can be found at oldeastindies.com