“Tír gan teanga is tír gan anam”, a country without a language, is a country without a soul. This age-old Irish proverb in the Irish language, or Gaeilge as it is called in that language, carries a profound truth that is often overlooked by the world. Far beyond the assumption of a predominantly English-speaking Ireland, lies a deep-rooted connection to their native language. This unwavering bond with the country’s mother tongue is the reason why Irish managed to survive throughout the years that Ireland remained part of the English imperial system until 1922. In this article, we will delve into Ireland’s commitment to preserving Irish through insights from Ireland’s Ambassador to Indonesia, H.E Mr. Padraig Francis.

During the inauguration of EUNIC Indonesia at Erasmus Huis, I encountered Mr. Francis delivering an impressive speech entirely in Bahasa Indonesia. As I listened to him, I realised the depth of his appreciation for language, and my mind wandered to an article I stumbled upon a couple weeks ago, recounting Ireland’s linguistic journey and how a native language that almost faded into obscurity managed to endure.

His speech sparked my curiosity to learn about the significance of language resilience, particularly in the context of his Irish heritage and its potential lessons for us Indonesians. Excited to delve deeper, I secured an interview with Mr. Francis for NOW!Jakarta.

Mr. Francis’ enthusiasm to share his insights on the subject mirrored my own. In our Interview, the first question I asked him was pretty direct, “How come your Bahasa Indonesia is so good?” In the realm of diplomatic exchanges, while many dignitaries do their greetings in the local language, many often revert to English in their speech and conversation. Yet Mr. Francis’ fluency went beyond pleasantries, and his answer to my question reflects how high he reveres language.

“For me, in order to understand a country, we have to learn its language. Because a lot of a country’s culture and customs are tied up within it. In Ireland, we believe that a country’s soul lies in its language”. He lamented the fact that currently the world had lost around a thousand languages and that this loss echoes the erasure of entire cultures and history, as they are always intertwined. “When those languages disappear, we will lose an entire culture, histories, literature, ways of living, and the folklores, they all go with the language…” shared the ambassador.

Such concern can be expected from someone who came from a country whose historical landscape is as turbulent as Ireland’s. Irish faced many challenges during British rule. Through the Statute of Kilkenny in 1367, English supplanted Irish as the language of administration and opportunity and it led to a decline in its usage. The Great Famine and subsequent emigration further eroded the hold of Irish, thus, it became associated with impoverishment. But against the odds, a cultural revival in the late 19th century, known as the Gaelic Revival, heralded a resurgence of Irish culture, folklore, and language, which also ignited the movement for Irish independence.

The aftermath of Ireland’s independence in 1921 witnessed the formal recognition of Irish as the first official language, with English as the second. However, economic incentives favouring English proficiency, particularly in urban settings, posed significant hurdles for the Irish language. Despite these challenges, committed communities along the west coast and a growing enthusiasm among parents for Irish-medium education for their children, have contributed to the stabilisation in the language’s decline.

In stressing the necessity of a living language, the Ambassador stated, “… [Irish] has to be living, it is not enough to just put it in a museum, people have to speak it in their daily lives and with as many people as they can.”

This is supported by the government through various state-funded initiatives, including Irish-language TV and radio stations, a thriving literary tradition, and the compulsory inclusion of Irish as a subject in schools.

What is even more important according to Mr. Francis is the grassroots initiative. He emphasised the significance of community-driven endeavours, namely the inception of Irish language schools initiated by local communities who are passionate about safeguarding their linguistic heritage.

When the Gaelic Revival happened in the late 19th century, it was the people who were the driving force behind it, a movement that endures to this day. “The role of people outside of government has been absolutely crucial,” the Ambassador said.

The conversation turned towards Ireland’s bilingual society. Mr. Francis highlighted the symbiotic relationship between the Irish and English languages that not only has enriched the literature scene but also propelled the cultural evolution of Ireland. In drawing comparisons with Indonesia, he shed light on the importance of multilingualism. “If you speak more than one language, you’re getting different views on the world. This is also one of the things that really impressed me about Indonesia.”

The Ambassador applauded Indonesia’s multilingualism, commending how Indonesians navigate between Bahasa Indonesia and local languages and dialects. He also stressed the importance of education and mass media in sustaining languages and cultures, “If people aren’t exposed to cultural production…they will gravitate to the other language”. He recognised the importance of pop culture in preserving and spreading interests in languages. Mr. Francis recommended the Irish language film “The Quiet Girl” as a compelling cinematic portrayal, despite Ireland’s smaller film industry.

When reflecting on Bahasa Indonesia’s evolution, the Ambassador found fascination in its modernity. He noted its uniqueness, being a language shaped during the country’s formation, linking its growth with the nation’s progress. He compared it to older languages, noting the accessibility of modern Bahasa Indonesian culture to the youth.

Drawing parallels between the resurgence of Irish and the birth of Bahasa Indonesia, Mr. Francis highlighted how Irish played a pivotal role in rekindling pride in Irish heritage during their struggle for independence. He pointed at how Bahasa Indonesia, emerging from the 1928 Youth Pledge, acted as a unifying force for a diverse nation. The Ambassador emphasised the significant role of young individuals in shaping their respective nations, noting, “It was the [effort of] young people creating the country that they were going to lead in, and that it was also pretty much a national project before the nation was even formed.”

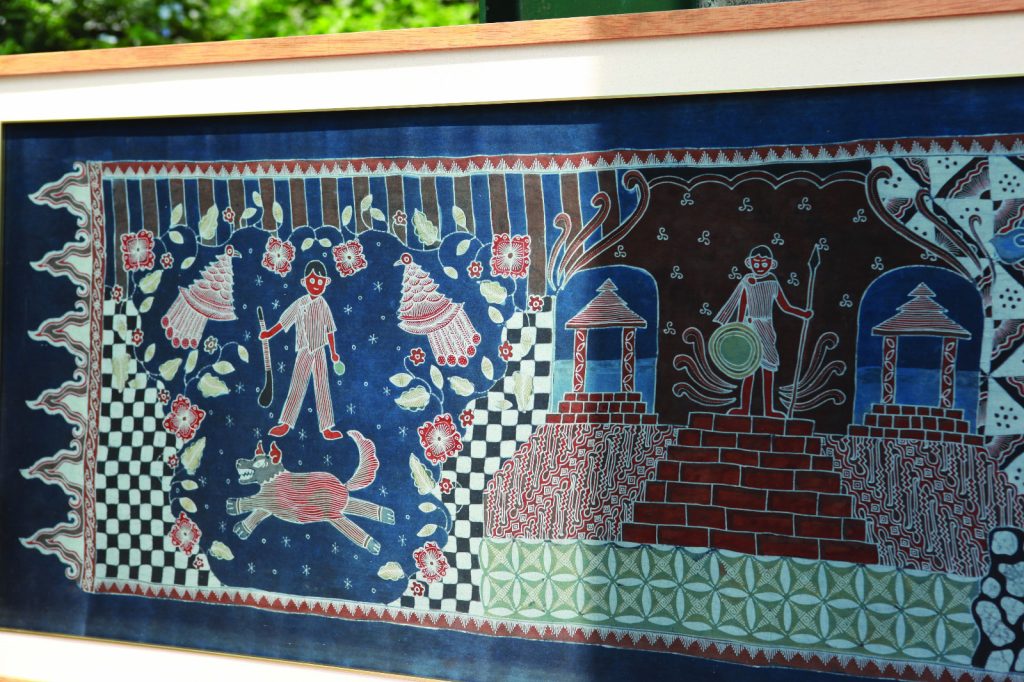

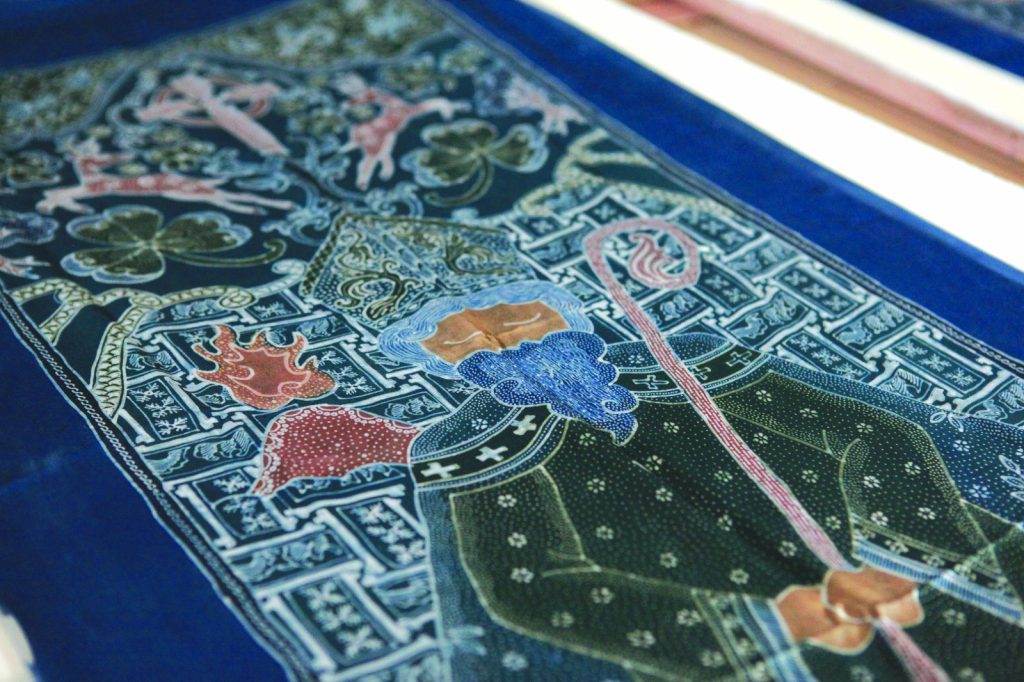

In reference to the cultural ties between Ireland and Indonesia, the Ambassador acknowledged the lack of strong cultural relationships, mentioning recognisable Irish products such as Westlife, U2, Guinness, and Irish whiskey that might not always be identified as Irish in Indonesia. In light of this, Mr. Francis emphasised his mission to amplify Ireland’s visibility and presence in the country. He discussed innovative initiatives such as an art project that intertwines Irish folklore into Indonesian batik art. He shared, “If people here in Indonesia are more aware of Dutch or Australian cultural connections, then we [the Irish Embassy] have to create new ones.”

Detailing the art project, he described it as a collaboration between an Indonesian artist, Vania Gracia from Bandung and batik artists from Jakarta, Pekalongan and Jombang to depict Irish mythology through batik motifs. This artwork aims to resonate with both Irish and Indonesian audiences, fostering a deeper understanding of each other’s cultural narratives. Referring to upcoming cultural events, the Ambassador revealed plans for St. Patrick’s Day and St. Bridget’s Day celebrations, including art exhibitions, poetry competitions and literary events centred on works by renowned Irish authors like James Joyce, Sally Rooney and Emma Donoghue.

Mr. Francis touched upon the profound impact of literature as a vehicle for cultural exchange and understanding, “Literature is an easier way [to spread cultural awareness] as it is very accessible for people anywhere in the world,” though he also showed concern on the challenges of limited availability of translations of Indonesian literature and drew parallel to similar problem in Irish literary translation.

Noam Chomsky, who is popularly known as the father of modern linguistics, once said; “Language is not just words. It’s culture, a tradition, a unification of a community, a whole history that creates what a community is. It’s all embodied in a language,” this resonates deeply with the enduring spirit of Indonesian and Irish people in safeguarding their linguistic heritage. Because they know that a language carries more than just words, it carries the soul of a nation.

Embassy of Ireland in Indonesia

World Trade Centre 1, L-14

Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav 29-31, Jakarta 12920

T:+62 21 280 94300

F: +62 21 521 1622

IG: @irandiadiindonesia