Article by Jean Couteau | Read his other articles in NOW! Bali

A very interesting exhibition has recently been held at the Bentara Budaya, Jakarta, between May 28 and June 8, showing the works of the Balinese artist Putu Wirantawan.

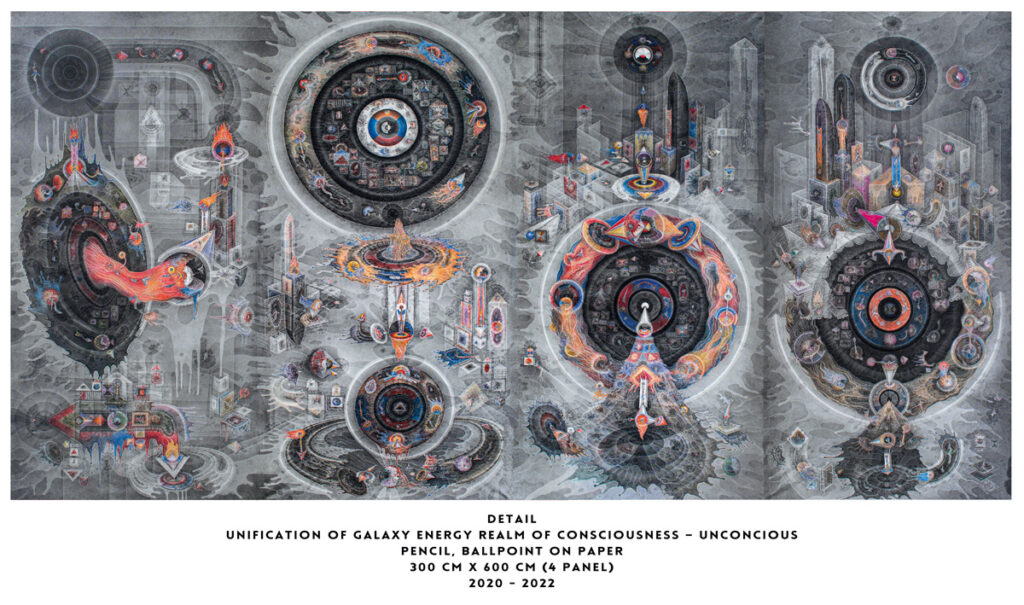

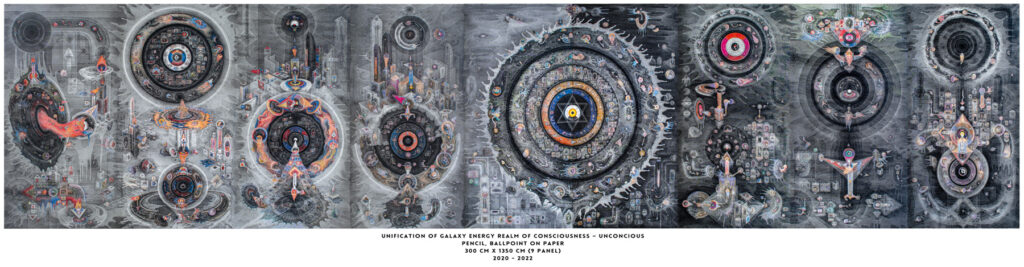

When gazing upon Wirantawan’s work, one is immediately struck—if not utterly overwhelmed—by elements that feel eerily alien to the familiar languages of contemporary art. These are not mere compositions, but vast symbolic terrains, immense in ambition and metaphysical weight. Within them, regularities—some sharp, others tapering, many ghostly and irregular—collide, fuse, and metamorphose in an unceasing dance. What first presents itself as chaos slowly yields a deeper order, emerging either through labyrinthine intricacies that draw the eye into a microcosmic abyss, or through swelling geometric spirals—each laced with delicate, obsessive detail—that hint at cosmic architectures endlessly expanding and collapsing. These structures are bound to one another like nested universes, each orbiting, spiralling outward, or disappearing into the minutiae of the next.

Circular forms dominate this trembling order. Amid the profusion of geometries, it is only the orbs—planetary halos, spheres, and cellular rings—that retain a sense of perfect regularity, as though endowed with the sacred task of sustaining cosmic harmony. Other shapes may gesture toward equilibrium, evoking echoes of geometrical symmetry, but under close scrutiny, their forms betray subtle instabilities—contours that falter, lines that hesitate, textures that breathe. What they offer is not symmetry, but near-symmetry—alive, and vibrating with tension. These figures pulse with a nervous energy: quivering globes, spiralled whirls, fractured orbits, and finely wrought geometrical scaffolds—all interlocked across micro and macro dimensions in a ceaseless churn, a celestial machinery caught mid-revolution.

His canvases are jungles of ink, alive with mythic velocity. Here, space is not a void but a fabric: there is no horizon, no single vantage point—only a fluid simultaneity, as if the artist has turned time inside out. The frame strains to contain the charge. One feels the drawing might spill beyond the paper and onto the walls, into the body, into the night. And yet, despite the absence of figurative forms, the eye waits for the emergence of beings, gods, elements, demons. But they never arrive. This absence intensifies the sensation of rising tension, in what Bateson would later call schismogenesis. Yet there is no catharsis, no mythic arrival—only the recursive spirals of becoming, the architecture of absence. Wirantawan’s work does not merely invite observation—it draws you in, and asks you to drift. There is no still point, only shifting centres. This is not composition in the Western sense, but incantation—an unfolding visual mantra where repetition births revelation, where meaning is not located but encountered through rhythm.

Then, almost imperceptibly, as one’s eye drifts further, at certain points within Wirantawan’s visual architecture, something more intimate appears: small, irregular specks—often in transparent hues—emerging not from the centre, but from its shadow. They stretch, tremble, and almost reach toward the edges. They suggest life—not life as form, but as a vibration, a possibility—poised on the edge of becoming, surging from void into presence, or fading from presence into void. This life never fully arrives—only its trace, its pulse, its rumour in the silence. As if, from the churn of chaos, order first emerged, and then life—or rather, the soul of life, wandering through the cosmic abyss.

To the viewer, Wirantawan’s constructions are jamais vu—never seen, never known. Miró or Klee may have touched the void, but Wirantawan’s void is of another substance: full, saturated, teeming. His informal elements buzz with the unborn, suspended between chaos and becoming. He captures not life itself, but the precise instant before life happens in the world—the breath held, the moment before the spark, the mystery before manifestation.

The spiritual reference is unmistakable, deeply rooted in Balinese cosmology. One might ask: is there a message from the artist? Indeed, one feels the echo of the dialectics of Bhuana Alit and Bhuana Agung—the microcosm and macrocosm—ancient concepts that bind the self to the vast orchestration of the universe in Balinese thought. Yet in Wirantawan’s visual world, this is no abstract speculation, but a visceral truth expressed at the tip of his pen: the self is a wandering speck within a greater spiral, animated not by ego, but by divine forces who weave both matter and meaning. The soul—fragile, almost anonymous—bears only the residue of karma as it drifts through dimensions both infinitesimal and immense. His works are instances of this unending process. The signs of a meditative search for oneness between the self and the universe.

“In the process of drawing,” says Wirantawan, “the forces, elements, qualities, and essences of nature and cosmos manifest themselves in every stroke of my pen, in direct connection with the deepest level of myself within. Joy, happiness, excitement—even tension, anger, fear, sadness, and pain—blend into one expression. These are the constant elements of nature and cosmic dualities. I express them in my work while at the same time endeavouring to neutralise them in the self. It’s not easy—far from it—but it is something I will keep learning and practising down to my last breath, because this is vital not only for the body, but also for the balance of the soul.”

This is art as meditation—when the self endeavours to rejoin the Cosmic Oneness. In both his mood and his work, Wirantawan presents himself as part of the very cosmic flux he evokes.

If you’re interested in Wirantawan’s work, you can see his work displayed at ARTSUBS, an annual art exhibition in Surabaya. Alternatively, you can get in touch with Wirantawan directly via Instagram.